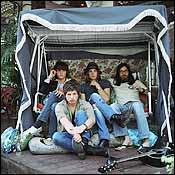

A Nashville quartet breathes new life into the dubious legacy of southern rock.

By Hans Eisenbeis

Why has the South never produced any decent punk rock? You'd expect confrontational punk statements to flourish in a region that has steeped itself for more than a century in the mythology of defeat, that seethes with backwoods narratives of sin and redemption, that has given us every kind of twisted and tortured literary creation from Faulkner's Snopes family to Flannery O'Connor's gallery of grotesques. Yes, there has been an embarrassment of "southern rock." But that is a saccharine blend of electrified country and stadium-rock bombast. Its highest expression, "Free Bird," is all about delusions of rebel grandeur. Southern rock is a sort of musical bully that looks good only when it lobs threats at weaklings and Canadians, like Neil Young. Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Allman Brothers, .38 Special-the South's Almost Famous moment came and went about 30 years ago, and it was artless. Why has the South never produced any decent punk rock? You'd expect confrontational punk statements to flourish in a region that has steeped itself for more than a century in the mythology of defeat, that seethes with backwoods narratives of sin and redemption, that has given us every kind of twisted and tortured literary creation from Faulkner's Snopes family to Flannery O'Connor's gallery of grotesques. Yes, there has been an embarrassment of "southern rock." But that is a saccharine blend of electrified country and stadium-rock bombast. Its highest expression, "Free Bird," is all about delusions of rebel grandeur. Southern rock is a sort of musical bully that looks good only when it lobs threats at weaklings and Canadians, like Neil Young. Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Allman Brothers, .38 Special-the South's Almost Famous moment came and went about 30 years ago, and it was artless.

Yet Kings of Leon manages to make it sound as though that whole dreary rampage of rebel posing never happened. The band's new release, Aha Shake Heartbreak , delivers a punk-rock mission statement in its first decipherable lyrics: "Rise and shine, all you gold-diggin' muthas," drawls Kings front man Caleb Followill. "Are you too good to tango with the poor, poor boys?" The music echoes the slogan's half-disheveled, half-revolutionary mood, with a drunken piano plonk weaving alongside a persistent bongo beat.

Regional politics aside, the Kings' belligerence is completely understandable. The band-which in suitably high-southern gothic style, consists of three brothers and a first cousin, all named Followill-debuted in 2003, with the energetic Youth & Young Manhood . It was received with underwhelming enthusiasm here in the States. At the time, critics were stimulated by a group of rich, bored, private-school kids called the Strokes, and they saw the Kings as low-rent copycats. This was unjust. The similarities were merely outward. The Kings played a raunchier, more soulful brand of garage rock; the low GPAs and halitosis were badges of honor reminiscent of the Ramones. They were earnest white-trash dropouts, after all, with a dad (named Leon, like his father) who drank bourbon and preached the Word, while practically living in a car. They were New South rejects, and their music sounded that way, and it was dirty good fun. It's hard to imagine any other band penning, to an admired girl, the inscrutable, timeless-sounding lament, "Hey! You're giving all your cinnamon away!"

Oddly, the band found an estimable critical following in Britain-usually the world capital of anxious pop trend-mongering. The Brits, finely attuned to the echoes of social class in pop music, took the Kings at face value. Of course, face value in a case like this is also more than a little deceiving: While Aha Shake Heartbreak showcases four feckless stoners speaking in their own shop-class patois, it also captures them playing alarmingly sophisticated pop. Like the best work of another underappreciated punk brothers act, Arizona's Meat Puppets, Aha is filled with often idiotic or lysergic punch lines delivered at a back-of-the- class mumble.

Still, this would make for pretty thin grits if it weren't accompanied by intensely rich, chiming rock. Consider "Milk," a schmaltzy pitch-perfect ballad, in which Caleb sings about what I take to be the Followill family's feminine ideal: "She saw my comb-over / Her hourglass body / She has problems with drinking milk and being school tardy / She'll loan you her toothbrush / She'll bartend your party." Still, the new release does feature at least one troubling sign of creeping self-consciousness, in the midst of a splendid, jangling rave-up called "The Bucket." Caleb abruptly starts in on the travails of spreading rock renown: "I'll be the one to show you the way / You'll be the one to always complain . . . I don't feel comfortable talking to you / Unless you got the zipper fixed on my shoe / And I'll be in the lobby drinking for two / Eighteen / Balding / Star!"

In moments like this you find yourself not only worrying about Caleb's hairline (a recurring theme) but also about whether the Kings' sense of twisted southern innocence can persist-not because it isn't genuine, but because the Kings' image as inspiring Dixie losers seems on a drastic collision course with the grim business of rock stardom. This was, after all, pretty much the dilemma-together with wicked management and a fearsome pill habit-that undid another southern King, across the state in Memphis. We should celebrate these new, uncorrupted Kings while we have still them. |